Lennart Nilssons stora vetenskapliga utforskning

Den svenske fotografen Lennart Nilsson lyckades fånga en värld som inte syns. Hans passion för vetenskap och rena konstnärliga talang belyste livets ursprung – och förändrade mänsklighetens uppfattning om sig själv.

ORD: ANDERS RYDELL, FOTO: LENNART NILSSON

Ett av de första fotografierna som bidrog till Lennart Nilssons internationella genombrott är fortfarande gripande att titta på. Det togs 1947 utanför Kvitøya i Barents hav, när den då unge fotografen reste med M/S Harmoni från Tromsø till Kvitøya för att föreviga en isbjörnsjakt.

På fartygets däck ligger en isbjörnshona med utsträckta lemmar och slutna livlösa ögon. Ovanpå henne kryper en isbjörnsunge, fortfarande vid liv men med ett rep virat runt halsen. Desperat och utmattad verkar den försöka få kontakt med sin mamma. Fotografiet skildrar deras sista omfamning. ”Det är en syn jag aldrig kommer att glömma”, förklarar Lennart Nilsson. Den som har sett fotografiet kommer inte att göra det heller, det är den typen av bild som etsar sig fast i både dina känslomässiga och visuella nerver. I den meningen är det ett typiskt Lennart Nilsson-fotografi – både dokumentärt, nästan brutalt naturalistiskt, men ändå präglat av skönhet och ömhet. Samtidigt sår det ett frö till ett återkommande tema i Nilssons fotografi. Livet – födelse, föräldraskap och död.

Lennart Nilssons fotografier från isbjörnsjakten publicerades först i den svenska tidskriften Se, men fick internationellt erkännande när bland annat Life Magazine delade dem. Fotografierna väckte både uppmärksamhet och hetsiga debatter. Vid 25 års ålder hade Lennart Nilsson redan format sin roll, hans uppgift var att dokumentera och berätta historier som världen aldrig hade sett förut. Få internationella fotografer har levt upp till denna uppgift som Lennart Nilsson har.

"Jag var fascinerad av att de hade händer, ögon och fötter. Det var fantastiskt."

För ungefär ett decennium sedan besökte jag Nilsson på Karolinska Institutet, och möttes av en livlig och nyfiken 88-åring som fortfarande fångade livets mysterier i bild – på den tiden, saker bortom den synliga världen. Ett par år före mitt besök hade han tagit den första bilden av sarsviruset, och om han levde idag skulle han förmodligen ha försökt fånga coronaviruset också. Trots att han var i höståldern agerade han som en ung och hungrig pressfotograf i de medicinska laboratorierna – ständigt på jakt efter nya upptäckter.

Nilsson växte upp med den stickande lukten av trycksvärta i tidningsredaktioner under 1930- och 40-talen. Han föddes 1922 och växte upp i Strängnäs. Hans far arbetade på SJ, den svenska tågtrafiken, men var också en entusiastisk hobbyfotograf. Lennart Nilsson fick sin första kamera när han var 12 år gammal och sålde redan sina fotografier till tidningar och magasin som tonåring. Han hade en unik känsla för fotojournalistik i kombination med en social gåva – han såg till att människor kände sig trygga framför hans kamera. Inte minst bland kändisar, som bidrog till att öppna dörren för den unge fotografen. Några av dem inkluderar Birgit Nilsson, Ingrid Bergman, Ingmar Bergman, Dag Hammarskjöld och Gustav VI Adolf.

Lennart Nilsson gjorde sig ett namn som en av Sveriges mest framstående fotojournalister. I slutet av 1940-talet började Nilsson genomföra olika expeditioner som fick internationell uppmärksamhet. En av dessa var den tidigare nämnda isbjörnsresan till Svalbard. År 1945 följde han barnmorskan Siri Sundströms dagliga arbete i den norra svenska vildmarken – där det enda sättet att nå födande kvinnor var genom längdskidåkning. En annan av Nilssons mest anmärkningsvärda resor var hans besök i Belgiska Kongo 1948.

|

Lennart Nilsson, Djungelfotografen Mayola Amici, Belgiska Kongo 1948 “Kongo”.

|

|

Hans intresse för vetenskap hade funnits kvar sedan ungdomen. Han samlade insekter och var fascinerad av makrovärlden, en värld som sällan dokumenterades i fotografier. Under 1950-talet utforskade han naturfotografi ytterligare. Från vattenfotografering där han dokumenterade livet under ytan till livet inuti en myrstack. Detta arbete resulterade i böckerna Livet i havet och Myror.

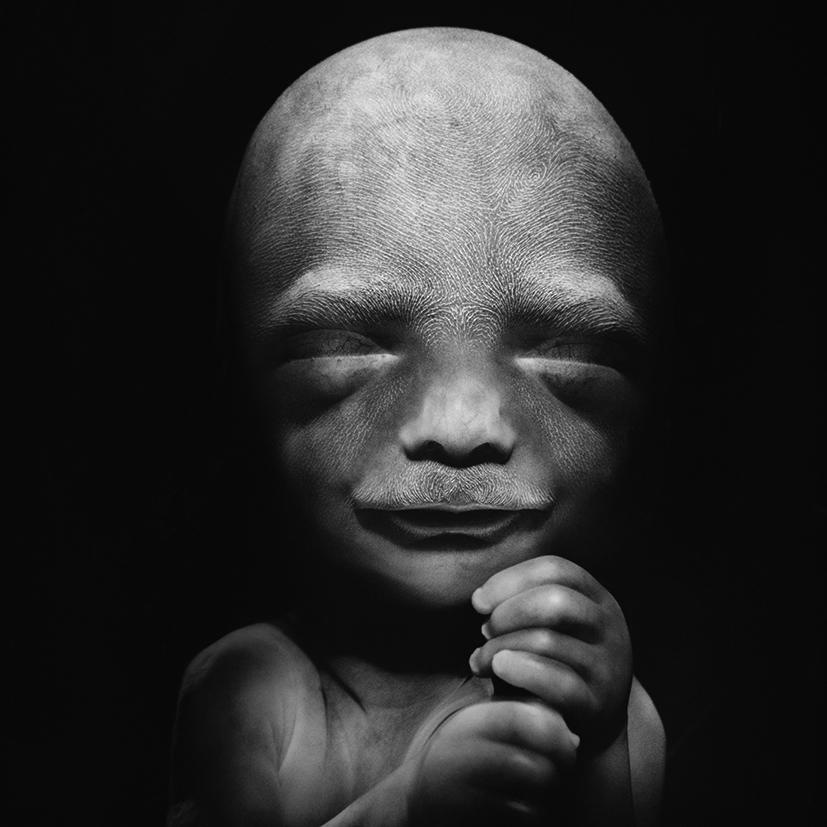

Men det var ett rutinarbete i början av 1950-talet som skulle bli hans livsverk. Under ett uppdrag på Sabbatsbergs sjukhus visades han embryon i formalin, som förvarades för medicinstudenter. Fotografen var fascinerad av varelserna som bara ett fåtal personer utanför sjukhus hade sett vid den tiden. ”Jag var fascinerad av att de hade händer, ögon och fötter. Det var fantastiskt”, mindes han. En läkare lät så småningom den ivrige unge fotografen ta med sig embryoburkarna till sin studio, där han fotograferade dem. Hans första bilder av embryona publicerades i tidskriften Se and Life 1953.

Ett par år senare började Nilsson dokumentera livets uppkomst genom fosters utveckling. Arbetet skedde i samarbete med flera sjukhus. ”Vissa sjukhus ringde mig när de hade något till mig. Ofta ringde de mitt i natten. Jag är väldigt tacksam att de lät mig göra det”, berättade Nilsson för mig när jag intervjuade honom många år senare. För att lyckas var Nilsson tvungen att ständigt anpassa sin fotografiska teknik, som att utveckla nya typer av linser. De flesta trodde att det helt enkelt var omöjligt att fotografera livets uppkomst – till och med redaktörerna på Life Magazine var tveksamma när Nilsson lovade dem färgbilder av ”de olika stadierna i mänsklig reproduktion, från befruktning till födsel”.

Det banbrytande arbetet resulterade i en av de mest berömda publikationerna hittills, när ett 18 veckor gammalt foster fick omslaget till Life Magazine i april 1965. Tidningens mångmiljonupplaga sålde slut på några dagar, och bilderna spreds över hela världen.

"Vissa sjukhus ringde mig när de hade något till mig. Ofta ringde de mitt i natten. Jag är väldigt tacksam att de lät mig göra det."

Precis som de första bilderna av jorden och månlandningen ett par år senare förändrade Nilssons fotografier mänsklighetens uppfattning om sig själv och synen på människans ursprung. Det var, i ordets rätta bemärkelse, banbrytande.

Senare samma år släpptes fotoboken Ett barn föds med text av läkaren Axel Ingelman-Sundberg. Det är en av de mest sålda fotoböckerna någonsin, med nya utgåvor och översättningar än idag. I samarbete med några av världens mest framstående vetenskapsmän och med ständig utveckling av teknik och utrustning släppte Nilsson många versioner av boken under de följande decennierna. De uppdaterade utgåvorna innehöll nyare och mer detaljerade fotografier. Nilssons långa arbete med att dokumentera livets uppkomst var inte bara innovativt och visuellt slående – det var också en teknisk och vetenskaplig uppfyllelse. Tack vare sitt engagerade arbete drev han den tekniska utvecklingen inom dokumentation av biologiska och kemiska processer med hjälp av mikroskop, endoskop, mikrolinser och svepelektronmikroskop. Dessa framsteg förde honom också djupare in i mikrokosmos i jakten på livets uppkomst.

Mellan 1965 och 1972 hade Nilsson ett specialkontrakt med Life Magazine. Under 1970-talet började han arbeta med rörlig bild – bland annat ett samarbete med TV-producenten Bo G. Eriksson.

Efter fyra års produktion släpptes filmen Livets mirakel 1982. Den visade människans ursprung och skildrade framgångsrikt äggcellens första delning. Livets mirakel tilldelades två Emmys. År 1996 vann hans film Livets odyssey också en Emmy.

|

Lennart Nilsson, Den vinnande sperman, 1990 ”Ett barn föds”.

|

|

Under 1980-talet uppnådde Nilsson en ny triumf – att fånga spermiernas resa in i ägget. ”Det var ett otroligt ögonblick. När spermierna trängde in i ägget började det skaka och röra sig som en planet. Moturs. Jag fick gåshud när jag såg det”, sa Nilsson efteråt.

Nilssons nyfikenhet och blygsamhet varade hela hans liv. Trots att han tilldelats några av de finaste priserna, som Hasselbadpriset och Emmy, och utnämnts till trefaldig hedersdoktor och statsprofessor, sa han: "priser betyder ingenting för mig." Det var hans ständiga önskan att utforska och berätta fotografiska berättelser som drev honom.

Sven Lidman beskrev Lennart Nilsson som ”någon mycket mer än en fotograf. Han hör faktiskt hemma i samma kategori som de stora upptäcktsresandena under förra seklet. Dessa resenärer var besatta av lusten att utforska det okända.” Passande nog var Nilssons mest poetiska utmärkelse kanske den i Voyager-ronderna som skickades ut i rymden i slutet av 1970-talet. Sonderna inkluderade fotografier av mänskligt liv, från befruktningen av äggcellen till dess delning. Dessa bilder skulle förklara för potentiellt utomjordiskt liv hur människor blev till. Sonderna är idag de äldsta människoskapade föremålen som har färdats längst i rymden. De färdas fortfarande genom Vintergatan och bär på Lennart Nilssons arv och arv.

Lennart Nilsson gick bort den 28 januari 2017.